Monday, October 17, 2011

Consumer Freedom?

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Greenpeace destroys wheat crop

The illusion of choice.

Recently in class we have been discussing the illusion of “choice” as consumers when it comes to our food. The finger has been pointed only at big corporate agriculture and the process of our food between the farmer and the grocery store; how the middle men in between are controlling what is being produced below them in line, as well as what is being sold ahead of them in the chain. While I won’t deny that there is truth to the argument, I realized today in class when we watched a horrendous video similar to that above, that corporate agriculture is incredibly far from the only entity working to control our choice in the stores. My first reaction was literally, “What the hell?!” I was livid. Activists do this kind of garbage all the time. But the bigger issue is that these organizations who claim to have consumers’ best interest in mind obviously do not. Organizations such as Greenpeace, PETA, The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), just to name a few, are political activist groups that have their own agendas to push and only give the impression they are working to better our lives as consumers. While I’m on my soap box, out of any donation to HSUS, a whopping 0% goes to any animal shelter or local humane society in the United States. Talk about propaganda! Airing those commercials with famous people and cute dogs and cats, claiming they help them!

Off my soap box (as much as I can…) for now and back to the idea of choice for a moment. We claim as consumers we are limited in our choices of what we can eat, but aren’t these group’s limiting them even more? PETA and HSUS both are trying to end animal agriculture for good. Not make it better, not improve the system, but end it. Period. So not only will we have to choose corn in everything else we buy, we will then be forced to become vegetarians. Now that’s a lack of choice. It won’t ever happen, but I’ll amuse my nonmeat consuming peers for a moment and hypothetically go down that road just, just briefly. At that point, there could be no fingers pointed at corporate agriculture for the lack of choice. At that point, those groups will have become even more powerful than those companies and will control everything we eat even more so than any single group does now.

Snap, back to reality, as I bite into my American grown hamburger. I suppose my main point here is that we cannot overlook the goals of these groups when we discuss the “illusion of choice.” They each have different goals, but ultimately, they want to limit the options of food for consumption we have available to us. Let the consumers decide if they want to eat GM wheat. In the video clip, the Greenpeace member says that they were trying to get CSIRO to be upfront and honest about the research they are doing. How can they do research to give factual information to the public about GMO’s if their plots are destroyed? These groups complain about a lack of long term research and trials of these new technologies, but then turn around and destroy the research plots and stations. Am I the only one who sees the contradiction here? There’s no way to do research on these crops and calm the fears of consumers if these groups—who are “looking out for consumers”—run around and ruin the research in progress.

Choice, to some extent, may in fact be an illusion to consumers. But the idea that big bad corporate agriculture is the guilty party is a stretch. In fact, consumers need to look in the mirror when they complain about lack of choice. But that’s a-whole-nother can of worms to be opened later.

Monday, October 10, 2011

South Central Farmers' Struggle for Justice

This video is a trailer for a documentary called The Garden, but it shows perfectly not only the disruption the farmers caused, but also how they utilized even more tactics than discussed in this blog during these peoples' struggle for justice. Watch it now, or when you get through the blog, or even just watch it and not read the blog, but it is a great clip for this.

The organization also relied on their ability to connect to outside people and gain support from celebrities and people with a lot of influence. Leonardo DiCaprio, Danny Glover, Willie Nelson, and Ralph Nader are just some of the many well-known people who supported the groups struggle. To the left is a picture of Daryl Hannah who actually chained herself to a walnut tree in protest of the eviction. Not only did the farmers have numerous celebrities and people of power, but they also had a lot of themselves. They had power in numbers and they showed it when they protested and had their night time candle-lit vigils. The farmers all came out in support of their cause and made a huge showing in the area around the garden. Not only did they show their numbers there, but as the case went through the courts, a strong majority of the farmers also appeared outside the court rooms and legal buildings where the hearings and trials were taking place.

The organization also relied on their ability to connect to outside people and gain support from celebrities and people with a lot of influence. Leonardo DiCaprio, Danny Glover, Willie Nelson, and Ralph Nader are just some of the many well-known people who supported the groups struggle. To the left is a picture of Daryl Hannah who actually chained herself to a walnut tree in protest of the eviction. Not only did the farmers have numerous celebrities and people of power, but they also had a lot of themselves. They had power in numbers and they showed it when they protested and had their night time candle-lit vigils. The farmers all came out in support of their cause and made a huge showing in the area around the garden. Not only did they show their numbers there, but as the case went through the courts, a strong majority of the farmers also appeared outside the court rooms and legal buildings where the hearings and trials were taking place. Monday, October 3, 2011

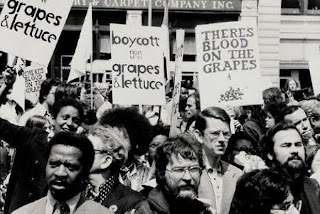

Farm Workers

Another part of the success of the Filipinos in California was that they were led by Larry Itliong and other very capable leaders. Some of these men had participated in the movements in Hawai’i and they were able to use those experiences to organize the people and lead them through the struggle. They struggled against white mobs and local police who would attack the picket lines and people involved in the movement. But what the Filipino’s did in response was a huge tactic in their favor. They stood up to the mobs. They decided that they had to become militant in order to not get pushed around and show that they were very serious about their demands and strikes.

Another part of the success of the Filipinos in California was that they were led by Larry Itliong and other very capable leaders. Some of these men had participated in the movements in Hawai’i and they were able to use those experiences to organize the people and lead them through the struggle. They struggled against white mobs and local police who would attack the picket lines and people involved in the movement. But what the Filipino’s did in response was a huge tactic in their favor. They stood up to the mobs. They decided that they had to become militant in order to not get pushed around and show that they were very serious about their demands and strikes.  Eventually the movement joined forces with Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association, which strengthened the entire movement for all races and their struggle against racism and the rich white land owners. When the two merged, a new union was formed; The United Farm Workers of America. This union still remains today, and is still very active in working for better working conditions and fair pay for its members. But besides the remaining union, this movement left an impact and ideals that can still be applied today. In agriculture now, migrant labor is a huge part of the labor force in fresh food production; tree fruit, vegetables, grapes, etc. In Washington, that labor is Mexican migrant workers. I think that movements like these have forced land owners and growers to pay fair wages to those migrant workers. These foods are usually grown in specific regions, so the workforce is centralized and close, making it easier to organize if they felt a need to. Granted, some people still do take advantage of them and pay them much lower wages, but that is changing. Credit should be given to the Filipino movement in that now growers are aware of what organized labor can do, and rather than try and suppress them and prevent them from organizing, most farmers treat them fair so that they have no reason to organize.

Eventually the movement joined forces with Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association, which strengthened the entire movement for all races and their struggle against racism and the rich white land owners. When the two merged, a new union was formed; The United Farm Workers of America. This union still remains today, and is still very active in working for better working conditions and fair pay for its members. But besides the remaining union, this movement left an impact and ideals that can still be applied today. In agriculture now, migrant labor is a huge part of the labor force in fresh food production; tree fruit, vegetables, grapes, etc. In Washington, that labor is Mexican migrant workers. I think that movements like these have forced land owners and growers to pay fair wages to those migrant workers. These foods are usually grown in specific regions, so the workforce is centralized and close, making it easier to organize if they felt a need to. Granted, some people still do take advantage of them and pay them much lower wages, but that is changing. Credit should be given to the Filipino movement in that now growers are aware of what organized labor can do, and rather than try and suppress them and prevent them from organizing, most farmers treat them fair so that they have no reason to organize.