In the book Roots of Justice by Larry R. Salomon discusses multiple movements throughout history and how organization of the people involved happened. When deciding what group or movement to focus this blog on, I chose the Filipino Farm workers because I felt like I could relate best to them. I hope being able to relate to this group will allow me to better understand their side of the issue and focus on why and how their movement was or wasn’t successful.

Without spending too much time discussing the idea of ‘success’ in movements, I think for argument’s sake, we can say that, for the most part, the Filipino farm laborers’ movement was successful. They faced serious adversity, and change was far from quick. But at the end of the day (figuratively speaking), they got “better than the union’s original demands” (Salomon, 2003, pg 18).

But why were they successful, and how did they accomplish what they wanted to? First off, why did they feel the need to try and make change? The Filipino workers were being shorted wages, poor working conditions, and were thought to be best suited for the “stoop” jobs because of their short build. Long story short, they demanded better pay, better work conditions, and equal rights as their white bosses and land owners—to end the discrimination against them. The movements in California started years after similar movements arose in Hawai’i and that gave these movements one of their biggest advantages; experience. Many farm workers had migrated to the main land looking for more work after they had partaken in the work stoppages and strikes in Hawai’i. When they were faced with similarly poor conditions on the main land, and after seeing success on the islands of strikes, etc, there was only one sensible thing to do.

Another part of the success of the Filipinos in California was that they were led by Larry Itliong and other very capable leaders. Some of these men had participated in the movements in Hawai’i and they were able to use those experiences to organize the people and lead them through the struggle. They struggled against white mobs and local police who would attack the picket lines and people involved in the movement. But what the Filipino’s did in response was a huge tactic in their favor. They stood up to the mobs. They decided that they had to become militant in order to not get pushed around and show that they were very serious about their demands and strikes.

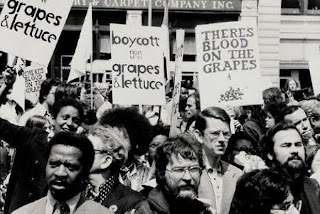

Another part of the success of the Filipinos in California was that they were led by Larry Itliong and other very capable leaders. Some of these men had participated in the movements in Hawai’i and they were able to use those experiences to organize the people and lead them through the struggle. They struggled against white mobs and local police who would attack the picket lines and people involved in the movement. But what the Filipino’s did in response was a huge tactic in their favor. They stood up to the mobs. They decided that they had to become militant in order to not get pushed around and show that they were very serious about their demands and strikes. It took multiple tries at organizing the labor force before they were able to create the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee. This was yet another advantage in the movement’s repertoire of tactics. The union grew large and quickly. A strike or work stoppage with all the union’s members caused a huge disruption and halted crop production and the growers were unable to successfully replace the workers and still make profits on their land. Salomon says that during the largest strike, lettuce growers lost up to $100,000 per day. Having the huge power in numbers, even in the face of attacks against them, they were able to put a lot of pressure on the land owners and growers. Because the Filipinos were truthfully good at working in the fields, the growers had to meet (and exceed) their demands for working conditions, pay, and equal rights as Americans.

Eventually the movement joined forces with Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association, which strengthened the entire movement for all races and their struggle against racism and the rich white land owners. When the two merged, a new union was formed; The United Farm Workers of America. This union still remains today, and is still very active in working for better working conditions and fair pay for its members. But besides the remaining union, this movement left an impact and ideals that can still be applied today. In agriculture now, migrant labor is a huge part of the labor force in fresh food production; tree fruit, vegetables, grapes, etc. In Washington, that labor is Mexican migrant workers. I think that movements like these have forced land owners and growers to pay fair wages to those migrant workers. These foods are usually grown in specific regions, so the workforce is centralized and close, making it easier to organize if they felt a need to. Granted, some people still do take advantage of them and pay them much lower wages, but that is changing. Credit should be given to the Filipino movement in that now growers are aware of what organized labor can do, and rather than try and suppress them and prevent them from organizing, most farmers treat them fair so that they have no reason to organize.

Eventually the movement joined forces with Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association, which strengthened the entire movement for all races and their struggle against racism and the rich white land owners. When the two merged, a new union was formed; The United Farm Workers of America. This union still remains today, and is still very active in working for better working conditions and fair pay for its members. But besides the remaining union, this movement left an impact and ideals that can still be applied today. In agriculture now, migrant labor is a huge part of the labor force in fresh food production; tree fruit, vegetables, grapes, etc. In Washington, that labor is Mexican migrant workers. I think that movements like these have forced land owners and growers to pay fair wages to those migrant workers. These foods are usually grown in specific regions, so the workforce is centralized and close, making it easier to organize if they felt a need to. Granted, some people still do take advantage of them and pay them much lower wages, but that is changing. Credit should be given to the Filipino movement in that now growers are aware of what organized labor can do, and rather than try and suppress them and prevent them from organizing, most farmers treat them fair so that they have no reason to organize.In certain parts of this state, migrant labor makes up not only the majority of the labor force, but also of the population. I would guess that in those areas, this—and other—agricultural movements have been taught and discussed much more than in Eastern Washington where I grew up. I had never heard about this particular movement before now, but I think looking back on the struggles and everything involved, it is clear to see that an impact has been left in agriculture today.

No comments:

Post a Comment